TensorFlow advanced applications with deep learning object detection, time-series analysis#

Objectives#

Understand the limits of deep learning models built to work with 3D imagery and variants that have been developed for 4D time series

Understand theory, use cases, and architecture options for time series modeling and change detection

Understand difference between semantic segmentation and object detection, labeling and modeling challenges with each approach

Cover R-CNN family, Yolo object detection families of architectures.

Semantic Segmentation with U-Net#

In Lesson 1a Introduction to ML Neural Networks and Deep Learning, we introduced the U-Net architecture, a popular architecture in remote sensing. U-Net has been onw of the most popular architectures for segmentation fo remote sensing images because:

Since U-Net is fully convolutional, it requires fewer parameters to train than models with multiple heads (R-CNNs) or models with many fully connected layers.

U-Net’s skip connections learns powerful features across many spatial scales that preserve high resolution features

the U-Net architecture can handle very high resolution images without saturating GPU memory, unlike other frameworks that learn many features per each section of an image.

U-net is therefore one of the most popular architectures for segmentation in very high resolution imagery (and low resolution imagery as well). At Development Seed, we’ve used CNN-based U-Net architectures for segmentation of supraglacial lakes https://developmentseed.org/blog/2022-12-13-segmenting-supraglacial-lakes

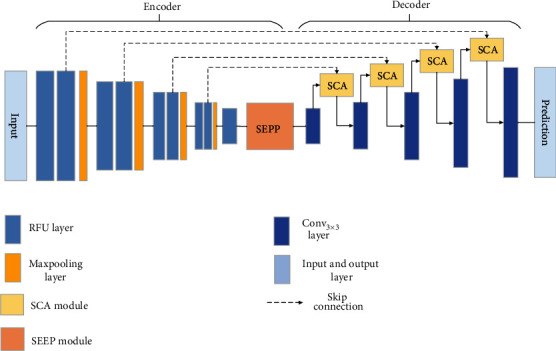

The traditional U-net architecture has been adapted and improved to work with high resolution 2D and 3D imagery. Of these SSCA-Net has been a popular option which uses self and channel attention.

Fig. 43 SCCA Image from “SSCA-Net: Simultaneous Self- and Channel-Attention Neural Network for Multiscale Structure-Preserving Vessel Segmentation”#

In the above figure, the SCCANet reflects the structure of a U-Net with some modifications:

The typical initial residual blocks in the encoder have been replaced by an RFU block, which is simply a 3x3 convolution followed by batch normalization and RELU.

They use a squeeze and excitation pyramid pooling (SEPP) module at the end of the encoder, which makes use of atrous convolutions and a spatial pyramid to account for multiscale features.

The decoder includes SCA modules that use self and channel attention to efficiently model long range dependencies in feature maps that are learned from previous convolution operations.

The SCCA model is very resource intensive to train, not just becaus eof the complexity of learning features for many different spatial scales at high resolution, but also because it requires large amounts of complex segmentation label data.

Vision Transformers and Masked AutoEncoders for classification and segmentation#

Of the multiple variants of vision transformers that have been developed since 2020, most recently Masked Auto-Encoders (MAEs) have shown strong performance, without requiring labeled data for pretraining! MAEs reframe the model training task from a fully supervised task that requires labeled imagery to a self supervised learning task that only requires imagery (but large amounts of it).

Masked auto encoders learn by randomly or selectively masking out parts of an input image, than learning to predict the contents of the masked portion, with the objective being to minimize the difference between the original input and the filled in masked result. Unlike traditional vision transformers, MAEs only encode the unmasked image patches, reducing compute and memory requirements for training large image feature encoders. The MAE decoder then accepts as inputs the embeddings from the MAE encoder, plus the positional embeddings of the mask patches that need to be predicted. The MAE decoder is very lightweight, and can be reformulated and quickly fine-tuned for specific downstream tasks, including image classification, segmentation, etc. (He et al. 2021).

Recent approaches in this vein include:

ScaleMAE - A Scale-Aware Masked Autoencoder for Multiscale Geospatial Representation Learning

SatMAE - Pre-training Transformers for Temporal and Multi-Spectral Satellite Imagery

Both architectures use vision transformers with masked auto encoders to attend to information across the spectral and spatial dimensions. Of these, Scale-MAE is more recent and shows favorable performance relative to SatMAE.

Fig. 44 Scale-MAE Image from “A Scale-Aware Masked Autoencoder for Multiscale Geospatial Representation Learning”#

Scale-MAE demonstrated higher knn-classification performance when fine tuned on different remote sensing benchmarks and used as a feature extractor. It also achieved higher semantic segmentation performance compared to other convolutional and MAE-based approaches. See the paper for details.

Scale-MAE has some important constraints:

the resolution of the sensor inputs must match, similar to other CNN and ViT architectures.

GPU memory use is large relative to traditional MAE

Scale-MAE took a long time to train and fine-tune.

As mentioned in Lesson 7b, vision transformers that operate on very high resolution image time series are very resource intensive to train and fine tune. In contrast, other approaches have explored discarding spatial attention and convolutional networks that prioritize learning spatial features altogether in favor of learning spectral and temporal features for change detection and segmentation tasks.

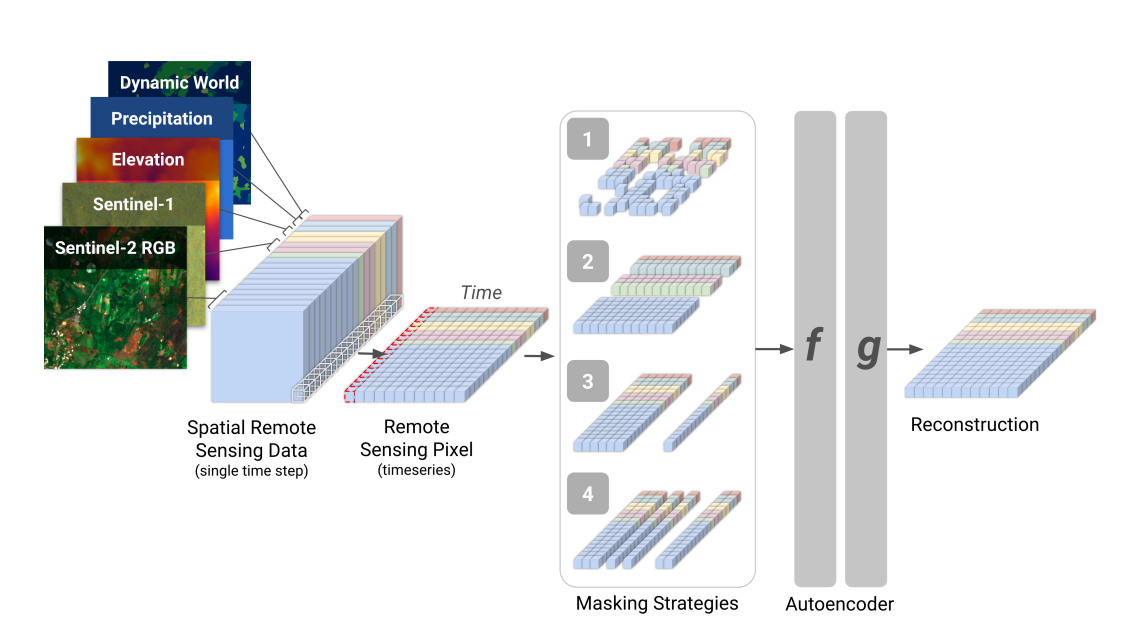

Time series and change detection without spatial features#

In contrast to vision transformers, Presto uses transformers to learn features for pixel time series, along the spectral and temporal dimensions. It does not learn textural information, discarding this expensive training requirement in favor of a more easily trainable and fine-tunable architecture relative to Sat-MAE and Scale-MAE. The paper makes direct comparisons to Sat-MAE and Scale-MAE on computer vision tasks, including single label and multi-label image classification, regression to predict algal bloom and fuel moisture intensity, and segmentation of complex cropland cover in different geographies.

Fig. 45 Presto Image from “Lightweight, Pre-trained Transformers for Remote Sensing Timeseries”#

Overall, Presto outperforms Sat-MAE and Scale-MAE on image classification and pixel segmentation. It’s worth noting that the Presto paper evaluated Sat-MAE and Scale-MAE by passing single time steps of 28x28 pixels per sample and evaluated Presto by passing more informative single pixel time series of 9 pixels per sample for training and inference. The results show that the time dimension is more informative than the spatial dimension, but this paper does not evaluate a MAE that learns spatial, spectral, and temporal features from an image time series (Tseng et al. 2023).

While we have not yet tested the performance of Presto, at Development Seed we have tested other models that operate on pixel time series. Our team has seen great success with TinyCD, a model using Mix and Match Attention that operates on pixel time series (Codegoni et al. 2022).

We used this model for burn scar change detection in the 2023 ChaBud Wildfire Detection Challenge, achieving a competitive IoU score on the public leaderboard of .7609, outperforming the DeepLabV3+ ResNet baseline which was.6765. Similar to SSCA Net, DeepLabv3 uses atrous convolutions and spatial pyramid pooling to learn spatial features at multiple scales.

You can view the TinyCD model implementation here: developmentseed/chabud2023

So what’s better, architectures that operate on time or spatial features?#

The short answer is that it depends on the problem. In the remote sensing domain, the temporal component is typically going to be more informative in resolution-constrained problems, where texture and other spatial features are less informative. If your detection target of interest has these qualities, spatial features like texture and edges may be particularly important and you may want to use a well established object detection or instance segmentation architecture fine-tuned from pretrained weights.

a well-resolved object with clear, simple boundaries

the object is not extremely disjoint

the object occurs within a well defined and limited range of spatial scales and aspect ratios

Using an object detection architecture gives you the benefit of being able to count and localize your phenomena of interest (for example, the number of agricultural fields or abandoned mines in a forest). With an instance segmentation architecture, the model can count, localize, and map the extent of the phenomena. Another advantage of object detection is that it is easier to make object detection labels in some cases than complex polygons for segmentation.

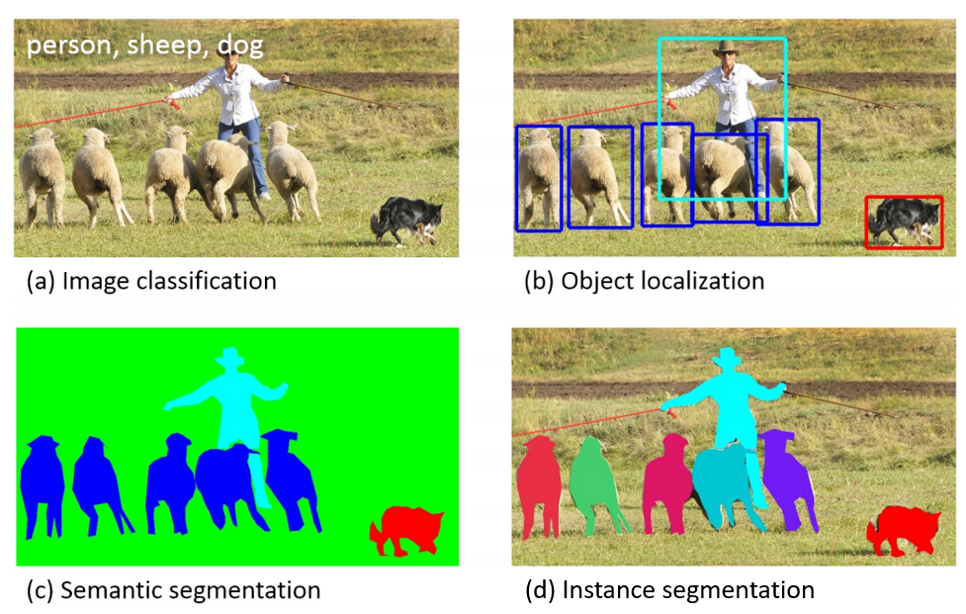

The following figure shows the differences between pixel classification (semantic segmentation), object detection, and instance segmentation.

Fig. 46 Computer Vision Detection Categories from Lin et al. Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context#

At Development Seed, we’ve used object detection in both remote sensing and non-remote sensing domains with success.

YOLOv5 for Object Detection in Wildlife Imagery and Remote Sensing#

We’ve tested and deployed Megadetector, a model pretrained on day and night wildlife imagery from many habitats around thw world. Megadetector is based on the YOLOv5 architecture, a great option for object detection as it is relatively fast to train and can run inference in near real-time, keeping GPU or CPU compute costs lower than slower architectures. All the code used to test model inference, export the model to a compiled format so it runs fast on a CPU, and to set up a containerized service for the model lives here: tnc-ca-geo/animl-ml

Of particular note with object detection is that the output of these models typically need some preprocessing steps. This is because object detection models make multiple predictions per image (multiple bounding boxes) instead of a single prediction (a segmented image, or category). A common step in object detection is to apply Non-Max Suppression (NMS), which aligns overlapping predictions and culls low confidence predictions. An example of NMS can be seen here. Bounding box outputs must also be rescaled if transformations are applied to image inputs. A common image transformation for object detection is letterbox, which preserves the aspect ratio of the input image by selectively padding and resizing the input. These same transformations need to be applied to the model output, the bounding box coordinates.

Some examples of YOLOv5’s use in object detection in remote sensing include:

Marine ship detection (Zhang et al 2022)

Aircraft Detection (Luo et al 2022)

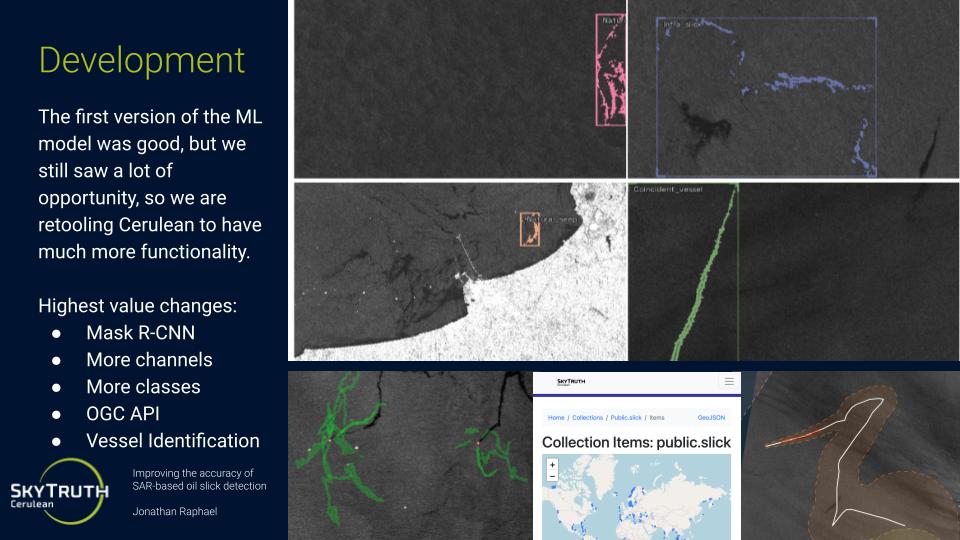

Mask R-CNN for Object Detection and Instance Segmentation of Oil Slicks in Radar Imagery#

While Yolov5 optimizes for speed, Mask R-CNN and related Regional Convolutional Neural Networks (R-CNNs) optimize for accuracy. We fine-tuned a Mask R-CNN model to map oil slicks emitted from shipping vessels as well as fixed marine infrastructure such as oil platforms, check out the abstract and presentation. Our imagery source, Sentinel-1, was resampled from 10 meters to approximately 70 meter resolution because our detection targets of interest were easily resolvable by Sentinel-1 at 70 meter resolution.

Fig. 47 Mask R-CNN detections true positive detections of anthropogenic oil slicks (Credit: Skytruth) from “Improving the accuracy of SAR-based oil slick detection”, https://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EGU23/EGU23-16932.html#

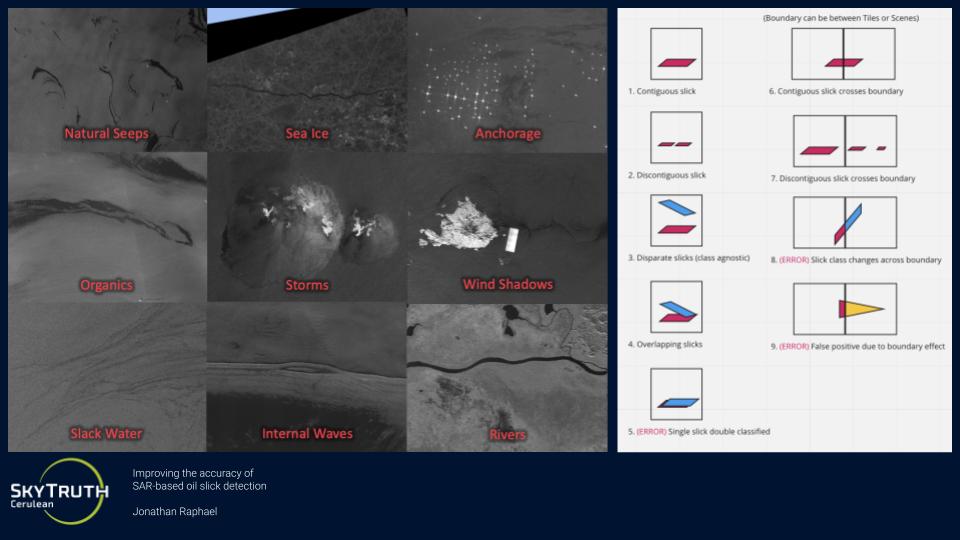

We compared results to a U-Net that produced semantic segmentation results, and found that Mask R-CNN produces less class confusion within individual oil slick events, but can hallucinate oil slicks where there are slick look-alikes, such as natural oil seeps, biogenic oils from algae blooms, seaweed, or ocean waves.

Fig. 48 Common False Positive Classes for Oil Slicks (Credit: Skytruth) from “Improving the accuracy of SAR-based oil slick detection”, https://meetingorganizer.copernicus.org/EGU23/EGU23-16932.html#

Semantic segmentation and instance segmentation models come with different trade-offs when it comes to the segmentation of oil slicks. While the oil slicks are visually distinct and easy to spot, determining their specific category source is more difficult. In semantic segmentation, these errors manifest as a mix of correct and incorrect pixel predictions within the same oil slick event, when all pixels should be of the same class.

On the other hand, Mask R-CNN enforces that all pixels of an object should be of the same class, but it can predict the wrong category, takes longer to train that a U-Net, and can predict multiple objects from complex, disjoint oil slicks that belong to a single event, which interferes with count accuracies.

See this presentation and abstract for more details.

Object Detection Example#

Let’s walk through an example for training a vision transformer based object detection model with Keras: https://colab.research.google.com/github/keras-team/keras-io/blob/master/examples/vision/ipynb/object_detection_using_vision_transformer.ipynb

References#

He, K., et al. (2021). Masked Autoencoders Are Scalable Vision Learners. arXiv preprint. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2111.06377

Tseng, G., et al. (2023). Lightweight, Pre-trained Transformers for Remote Sensing Timeseries. arXiv preprint. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.14065

Codegoni, A., Lombardi, G., & Ferrari, A. (2022). TINYCD: A (Not So) Deep Learning Model For Change Detection. Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/2207.13159