2025 was a year defined by collaboration. We wrote about the tools we built, the standards we helped strengthen, and the partners and communities who made that work possible. We reflect on those stories and how they are shaping our focus for 2026.

If there was a single throughline to Development Seed’s work in 2025, it was this: progress happens fastest when it’s shared.

Across our blog this year, we wrote about tools, standards, experiments, and people. With scientists, designers, engineers, and decision-makers working to make sense of a changing planet using better data and more thoughtful systems.

Here's a brief look back at 2025 through the stories we chose to tell.

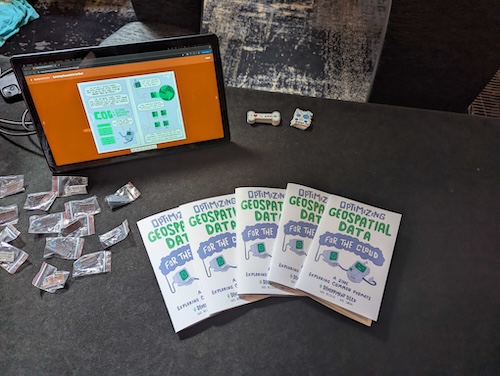

Spending time with friends during our Zine Launch Party in February.

Much of what we shared focused on the less visible, but deeply important work, of strengthening shared infrastructure.

eoAPI continued its shift from proving what was possible to supporting what is dependable. In 2025, the emphasis was on stability, deployment, and day-to-day operability, shaped by teams running eoAPI in real environments with real constraints. The focus moved from standing up services to maintaining them over time.

Across the STAC ecosystem, the conversation broadened. Efforts around STAC-GeoParquet, STAC APIs, and tools like stac-map reflect a shift away from how data is stored and toward how it is discovered, queried, and shared across tools and organizations. This work is less about any single implementation and more about lowering the cost of participation in the ecosystem.

Zarr followed a similar path. Work around Sentinel data, EOPF workflows, and multidimensional access patterns reflects an ecosystem still taking shape through shared experimentation, community feedback, and practical tradeoffs rather than a single prescribed solution.

None of this happened in isolation. It was shaped alongside partners across ESA and NASA programs, open-source maintainers, and organizations building production systems on shared standards every day.

Data in Service of Decisions

In 2025, more attention turned to what happens when infrastructure meets real use.

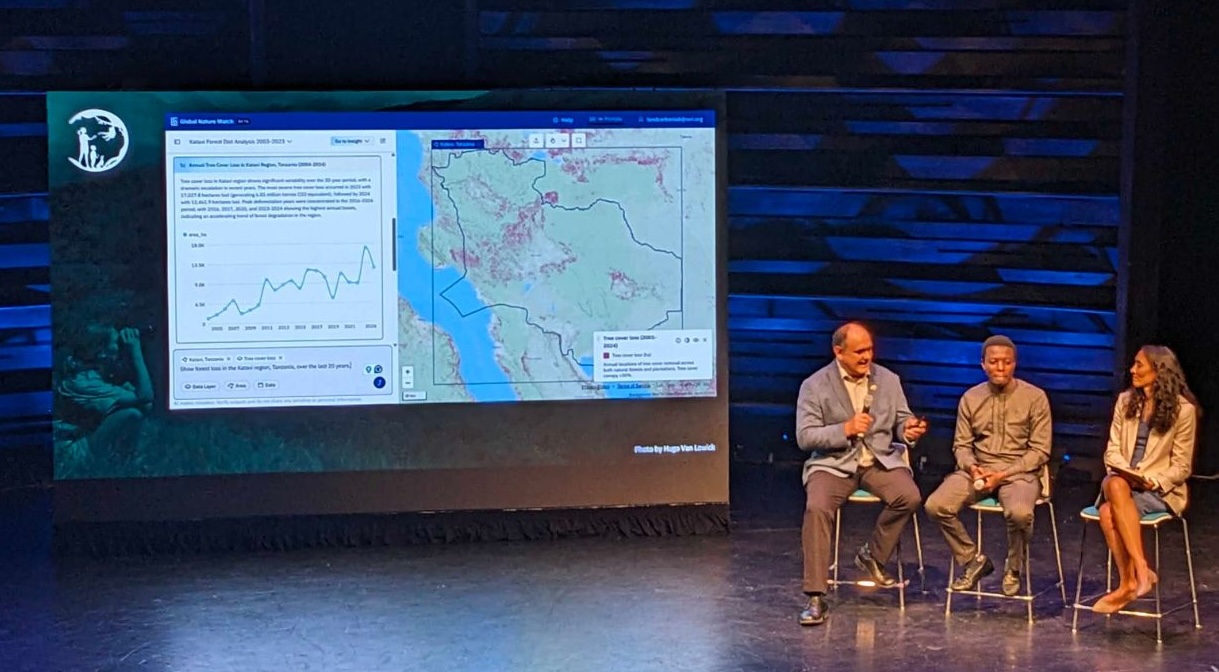

Global Nature Watch, developed with Land & Carbon Lab and convened by World Resources Institute and Bezos Earth Fund, is a clear example. Years of scientific investment and collaboration come together in a platform designed to make environmental data accessible and usable. The emphasis is not just on pipelines and models, but on trust, clarity, and responsible design.

Other applied tools and workflows explored similar questions, like fire exploration, and urban accessibility to science storytelling. Across these efforts, a consistent question emerged: who is this for, and what decision does it support?

That question shapes how interfaces, defaults, and documentation are designed, and why lowering barriers to complex Earth data does not have to mean oversimplifying it.

Experiments and learning in public

Not everything shipped in 2025 was polished, and that was intentional.

Through the Groundwork series (2, 3) and other exploratory efforts we surfaced ideas still in progress. Early tooling experiments, new visualization approaches, and open questions were shared as part of an ongoing learning process including work like we did for the Google Earth Engine QGIS plugin. We believe that learning in public strengthens the ecosystem by inviting feedback and reducing duplicated effort.

The Cloud-Native Geospatial Data Zine was also an experiment in how to rethink how we share technical information. The zine functions as a learning artifact rather than a product. It explores how people engage with technical concepts, how visuals shape understanding, and how storytelling can support broader adoption of open tools and standards.

We shared our zine at many of the conferences we attended this year.

The people behind the work

Several stories this year focused not on software, but on people.

Team spotlights like Gjore & Kevin highlight the range of backgrounds and perspectives that make this work possible. From cloud engineering and front-end development to science and systems thinking, these stories underscore that open-source ecosystems are sustained by people showing up consistently.

We also reflected on our role in the community, not just as builders, but as collaborators and stewards.

A year shaped by community

Looking back across the work shared this year, what stands out most is how many of them are fundamentally about shared ownership.

Brianna & Alex attended the GeoJupyter Hackathon this summer in Berkeley, California.

Shared standards. Shared tools. Shared responsibility for maintaining the systems we all depend on.

From Global Nature Watch to STAC and Zarr tooling, from lightweight infrastructure experiments to early-stage explorations, the work we documented this year reflects an ecosystem growing together. Progress came not from any single breakthrough, but from years of accumulated effort—maintainers refining specifications, partners aligning around common goals, and teams choosing long-term sustainability over short-term wins.

We’re grateful to the collaborators, reviewers, users, and open-source communities who shaped the work we wrote about this year—and the work behind the scenes that didn’t make it into a blog post.

Lily and Wei Ji were in Vanuatu this summer teaching a series of workshops.

Looking ahead to 2026: closing the last mile

As we head into 2026, the question is no longer whether new technologies can be applied to geospatial problems. That work is already underway.

The harder question is how and whether they should be applied.

Our work in 2025, especially with partners like Land and Carbon Lab on Global Nature Watch, reinforced a simple truth. AI is not a shortcut. It is an interface. When it works, it works because the data, infrastructure, and standards underneath it are solid. When it fails, it fails for the same reasons.

We see 2026 as a year of closing the last mile.

That means moving GeoAI from promising demos into systems people can trust. It means treating cloud native architectures as table stakes. It means continuing to invest in open standards like STAC, Zarr, and GeoParquet because that is how real ecosystems scale.

It also means being honest about tradeoffs. AI consumes energy. It introduces new risks around confidence and interpretation. Not every problem needs a model, and some problems are better solved with simpler tools.

These are not abstract questions. They shape what gets built and who it serves.

As we move into 2026, our focus is on building carefully, asking better questions, and continuing to work in the open with partners and communities who share that responsibility.

If you are excited as we are about the future of modern open geospatial, get in touch.

What we're doing.

Latest